5 hours ago

Guillermo Del Toro Builds a Handsome, Grand ‘Frankenstein’ That Is All His Own

Lindsey Bahr READ TIME: 7 MIN.

Guillermo del Toro has been telling monster stories for as long as he’s been making films. A romantic with keen appreciation for the macabre, his creations are things of strange beauty, haunting, poetic and unforgettable. It’s no wonder his earliest love was “Frankenstein,” first the Boris Karloff film, then the novel, which set him on a path to becoming a filmmaker.

Don’t expect a by-the-letter adaptation of Mary Shelley’s immortal story, however. This “Frankenstein,”in theaters Friday and streaming on Netflix on Nov. 7, is an interpretation, a reading of that tale of the brilliant scientist and his creation, from one of our most visionary filmmakers who has made it very much his own. Is it his best? No, but it overcomes the handicap of the dreaded passion project that has befuddled more than a few greats before him.

It is a story about stories, about fathers and sons, innocents and monsters, and the madness of creation. And while del Toro lets both Victor Frankenstein (Oscar Isaac) and the creation ( Jacob Elordi ) tell their sides of the tale, this is not exactly neutral. Del Toro has always loved the “monster” and, perhaps because of that love, has stripped him of the complexities that made Shelley’s character so fascinating. Here, the creation is an innocent, subject to the same impulses of rage as a toddler. But, thankfully for parents everywhere, toddlers can, generally, be contained. This creature’s strength is superhuman, which is unfortunate for anyone who happens to provoke him. He doesn’t just kill — he skins, he tears jaws off, he tosses grown men with a velocity that suggests they weigh little more than a baseball. It’s all quite grisly.

But neither he nor Victor is without reason — all men are products and victims of their own fathers, whose mothers and mother figures (in both cases, Mia Goth, a metaphor that is perhaps a little too on the nose) cannot protect them, del Toro tells us, and these two are particularly doomed.

Isaac is delightful as Victor, brilliant, egotistical and with a flair for the theatrical, a defiant outsider consumed with the idea of making life from death. He’s obsessed with surpassing his father (a menacing Charles Dance), intellectually and scientifically, and the idea that he might have been able to save his late mother. He’s relegated himself to being a mad loner, a proud exile who has softness only for his brother William (Felix Kammerer) and William’s fiancee, Elizabeth (Goth), an excellent foil for Victor’s hubris. While Elizabeth might embody something of a feminine cliché whose instinct is to nurture and protect the creation, rather than mold and control him, Goth imbues her with sharp wit and wisdom. She’s the kind who might even be able to save Victor from himself (or at least that’s what he thinks), if only she weren’t marrying his brother.

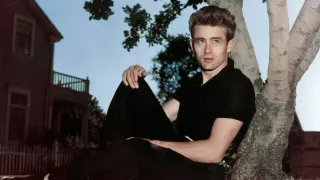

And then, of course, there is the creature. There are no bolts in this head: Victor's design is that of an artist attempting to make a marble Adonis, but whose stitches never quite disappear and whose scraggly hair suggests the eerie undead. In Elordi’s hands, the creature is a sensitive soul tortured by his own existence. His default is gentleness, but his survival instincts are very real, and very violent. Victor quickly comes to hate his creation because he believes it dumb and he leaves it to fend for itself.

If the first half the film is a symphony of crazed creation, the second is one of discovery, a coming-of-age story for a monster who just wants a companion but who is only met with hatred, disgust and violence — save for an old, blind man (David Bradley) who, like Elizabeth, sees a gentle soul. The creature is also quick to learn under a kinder tutor, which proves to be a double-edged sword as he comes to understand the nature of his being and the curse of eternal life. It’s all very spelled out on our behalf.

The gothic grandeur on display is familiar territory for del Toro, though he’s often had to stay within certain confines. Working with many of his regular collaborators on “Frankenstein,” it seems no expense was spared in this elaborate, maximalist world-building (production designer Tamara Deverell), from Victor’s lavish childhood estate to the abandoned irrigation plant that will become his laboratory. The romantic, beautiful, utterly impractical costumes, too, (overseen by Kate Hawley) could fill a museum, not to mention all the severed limbs. It all comes to electrifying life with Alexandre Desplat’s appropriately epic score.

Everything about “Frankenstein” is larger than life, from the runtime to the emotions on display: The empathy, the anguish, the rage, the regret. And it can be a bit exhausting, too, a lifetime of dreaming jam packed into 149 minutes. Hopefully del Toro is at peace with his creation: It might not be masterpiece material, but it has a soul and is an undeniably beautiful, worthwhile addition to the canon.

“Frankenstein,” a Netflix release in select theaters Friday and streaming on Nov. 7, is rated R by the Motion Picture Association for “bloody violence, grisly images.” Running time: 149 minutes. Three and a half stars out of four.